Tigers

This article originally appeared in the July 1987 edition of Harpers and Queen.

I was once a spectator at one of the last great tiger shoots in India, before the sport was abolished in 1970. In the hills of Madya Pradesh, buffalo were tied up overnight to attract the prey, and when one was killed, hundreds of tribals would beat out the valley towards a waiting gun, hidden up a tree. I was too young and innocent to be shocked by the sport, and sometimes I eagerly joined the beaters in thrashing through the valley.

But now I am happy to remember that, on this occasion, the hunters were not successful, even though there were plenty of tigers in those hills. Their lack of success was caused by the severe constipation – a surprisingly frequent complaint among Indians – of the principal gun and his substantial entourage. It took so long each morning to wheedle them out of their lavatories into the machans that, by the time they arrived, the tiger had abandoned the kill and gone from the valley.

Almost everyone (including my former host) now agrees that shooting tigers is unacceptable. Certainly some of the statistics make depressing reading today. One maharaja of Udaipur boasted of killing more than a thousand, and the Maharajkumar of Surguja wrote to George Schaller, author of The Deer and the Tiger, saying that, ‘my total bag of tigers is 1,150 (one thousand one hundred and fifty only)’. Despite these horrifying figures, all the experts agree that the critical reason for the tigers’ decline has been loss of habitat, not shooting. Each animal roams over an enormous range (often more than 25 square miles) and therefore vast tracts of undisturbed forest are indispensable for sufficient prey and a genetically-viable breeding unit. However, during recent decades their habitat has been massively reduced by human over-population and the consequent destruction of forests and over-grazing.

At the turn of the century, estimates put the number of Indian tigers at about 48,000. By the time of the tiger census in 1972 this had shrunk to well under 2,000. At this level, of course, the depredations of sportsmen, and even more so of poachers, become a serious matter. It looked as if the Indian tigers might be going the way of the Balinese, Caspian and Javanese species, all of which became extinct during this century – or of the Indian cheetah, which became extinct when the last three were shot in 1948.

However, since the inception of Project Tiger in 1973, vigorously backed by the Government of India, the stock of tigers has more than doubled. In Kanha, the first sanctuary I visited, 940 square kilometres now hold about 80 tigers, where fifteen years ago there were only 30. In this huge national park in the highlands of Central India, I stayed in Kipling where each morning I was woken at 5.30 by Nabi, an even-better-than-Jeeves steward, with a cup of tea and bucket of hot water. Then, because these highland mornings are freezing, I piled on several jerseys before speeding off in an open-sided jeep into the reserve. Kanha is mainly a deciduous tropical forest of tall sal trees which give it a semi-European aspect; a more tropical character is provided by the numerous dried-up nullahs (river beds), and these, along with its park-like meadows, endow it with a special beauty. We drove past a mist-covered lake to the first patch of meadows, where a jackal lay sunning itself in front of great herds of the tigers’ favoured prey, antelope and deer. However, after much searching we returned to camp without a glimpse of the elusive predator.

It is the custom at Kanha to spend about three hours in a jeep in the morning (you are not allowed to walk in the reserves), breaking this with a halt for breakfast, then a return to the camp for lunch, followed by a read and a snooze. Evening was the time for elephant rides, and it was these I enjoyed the most. The elephant’s mahout sees his principal role as tracking a tiger, but, whether you see one or not, the rambles through the nullahs, elephant grass, bamboo clumps and sal forest in the glow of the late afternoon sun are memorably beautiful. And it is a joy to watch a skilful mahout following the tracks of a tiger.

On the first evening, my mahout followed some clearly-marked footprints along a sandy trail. Then the path wandered off into the forest, but he was still able to follow the track, while I could distinguish nothing at all. Occasionally, he clambered down the bent leg of the elephant to peer at nondescript drifts of leaves, which seemed to hold evidence that we were approaching a tiger. Suddenly we heard the alarmed chatter of langur monkeys; almost simultaneously two peacocks hurtled upwards out of a clump of tall reeds. There was definitely a tiger nearby. Round and round we went, but the sun was setting, and soon we had to return without sighting our quarry.

On my second evening, we found a troupe of wild pig, huge numbers of spotted deer, a yellow jungle cat gazing up from a matching clump of dried grass, and a spectacular battle between a single jackal and a flock of vultures, who were trying to steal its kill. We were again returning home tigerless, when we heard the shrill alarm bark of a spotted deer. The mahout halted the elephant. The call was repeated. He paddled the elephant’s neck with his bare feet, and we moved slowly in the direction of the call. Then came the deeper alarm-call of the sambar (a surer sign of a tiger, because the sambar is a larger, more confident deer). The mahout thwacked his stick over the elephant’s head. It moved a little faster. Then he pulled out a curved driving-iron (its design identical to those in seventeenth-century miniatures), which he dug ferociously into its skull. The elephant picked up a surprising turn of speed. It picked its way across a deep nullah, crashed through the towering bamboos until we emerged into a forest, where the mahout brought it to a standstill, and pointed at a crow which was gazing fixedly into a clump of greenery.

Staring at the clump, I discerned only an orange flower which, as we came closer, turned out to be a patch of tiger fur. At our approach, the huge lustrous animal eased itself out of the bush and walked a few paces to a fallen tree trunk, along which it stretched out like a domestic cat, scratching its claws deep into the wood.

This tiger, like most I saw, was indifferent to humans, so long as they were riding an elephant. A few days before, an elephant-mounted party of four Japanese had come eye to eye with a tiger perched on a ledge within twenty feet of them. Videos whirred, cameras clicked, the tourists jabbered: the tiger remained unperturbed. Suddenly, however, the tiger looked over their shoulder, and bolted away in alarm. It had spotted a wandering priest who was walking along a path more than two hundred yards away.

My luck continued the following morning. We had only just driven into the reserve, when the driver halted the car and whispered ‘tiger’. One had been walking towards the road. It was now crouched down, and all I could see were two tell-tale blobs of white on the inside of its curved ears. We turned off the engine and waited for it to move. The watching animal showed no signs of stirring, so we passed the time by listening to the suggestive forest sounds, which are at their best in the early morning. At first there was only the howling of jackals, but soon this was replaced by a great cacophony from the birds – the caterwauling of peacocks, the monotonous crescendos of the brain-fever cuckoo, the chiming of coppersmiths, the chattering of babblers, the barnyard calls of jungle-fowl, the screeching of grey hornbills, the twitter of sun-birds, and the squawks of blossom-headed parakeets.

The tiger was still motionless when we heard the ominous roar of an approaching convoy of tourist-filled jeeps. Swivelling our binoculars round to the tree-tops, we pointed at non-existent birds, and earnestly consulted ornithological field guides. The convoy obediently passed on.

My next Tiger Reserve, Ranthambore, is probably the easiest place in the world to see wild tigers. It is set amidst the semi-desert of Rajasthan, and, for a tiger sanctuary, the landscape is unusually open. But it is by no means the most satisfying place to see the great predator, for the reserve is so popular that you are unlikely to be left alone to your viewing: and the tigers are so accustomed to jeeps that they have become almost too tame. It is a paradise created, and a paradise destroyed.

On the edge of the main lake at Ranthambore, there is a small Jaipur-pink lodge, the Jogi Mahal, which, were it well-managed, would be one of the world’s most enchanting hotels. But be warned: any reservation is meaningless, for sometimes the lodge ceases to be what is normally regarded as a hotel, becoming instead a hostelry for VIPs. Most days I met guests who had been turned away, even though they had confirmed reservations. As there are very few lodges permitted inside game parks, the demand is great.

Although my own booking had been made three months in advance, I was ousted by a host of VIPs who descended upon the reserve to pass the festival of Holi. (In India, the term ‘VIP’ covers a wide variety of the rich and powerful. What we call ‘VIPs’, they call ‘VVIPs’.) Among those who ousted me was a young Kashmiri princess, who arrived with her own guru, an Englishman with the face of an especially benevolent insurance broker. I later spotted him, dressed in pink robes and brown beads, sitting sedately in the front of a jeep; the princess found herself perching less comfortably in the back.

When the VIPs went on their way, I moved into the Jogi Mahal and was left in possession of the unbeatable view from its wide Mogul-inspired balcony. The great lake was covered with bright green lotus leaves and white lily flowers, all streaked with patches of purple weed. On one side, tall curving coconut palms framed the lake in the manner of Daniell, and on the other side, spotted deer browsed nervously at the water’s edge. A herd of sambar wallowed up to their necks, feeding on lotus leaves.

Despite the frequent VIP presence in the Jogi Mahal, it is not quite as well run as Fawlty Towers. Cigarette butts litter the bathrooms, and the beds are never made. One evening the cook got drunk and tried to stab the gatekeeper. I reported this drama to the field director, who replied, ‘Always he does these foolish things. It is very bad’. And that was the end of it – except from then on, I frequently assured the cook (who was never without his knife) that his food was delicious, and, no, I didn’t mind at all if breakfast was an hour late.

I wasn’t too upset about this hiccup, for when one suffers the problems and discomfort found in most of the interesting parts of India, one should rejoice: this is what prevents the whole continent from being overwhelmed by tourists. And, happily, there are other aspects of the game lodges to deter the fastidious. At Ranthambore, a three-foot snake (I think a harmless water snake) slithered in and out of the bedrooms; at another lodge, a rat in the rafters regularly showered its droppings over my sleeping head. One guest complained about a nesting mouse that each night tugged at her hair, and in a visitors’ book I found a poem:

Not a tiger burning bright

But a lizard in my bed at night

God it gave me such a fright

And worse, I wasn’t even tight.

On my first morning at Ranthambore, I was taken out in a jeep by Fateh Sing, the field director, famous for having improved the reserve by ejecting more than twenty villages (allegedly with their consent), and for having been ferociously attacked during a dispute with locals who wished to graze their cattle within the reserve. Within half an hour he had led me to three fourteen-month-old tiger cubs who lay resting in the shade, while their mother hunted in the valley below. It must have been a difficult hunt, because frequent alarm calls from monkeys and deer drifted up to us. Fateh Sing said the cubs would stay put for an hour or two, until their mother called them into the valley.

I had many fine and close sightings of tigers at Ranthambore, but only really ever enjoyed them on the occasions when I was alone. This was rare, for there are few tracks and too many (usually noisy) visitors; the tracks become crowded because – quite rightly – ordinary visitors are not allowed to leave them. The numerous VIPs are, of course, allowed to disobey this rule, and only a saint wouldn’t rage when they crash past you into the undergrowth.

Despite these horrors, Ranthambore is magical when you are alone. Among the lakes, decaying fortifications, pleasure-domes, and mausoleums, you see game mingling as closely as they would in the Garden of Eden. An open-mouthed crocodile basks at the edge of the lake, while only feet away, a spotted deer grazes next to a black-necked stork, who in turn ignores a glossy ibis. Just nearby, a turtle’s head is thrust up, while a splash alerts you to an Indian shag plunging for an enormous fish half its size. Once, while admiring a pond heron perched on the back of a wallowing sambar, I was startled by a dazzling flash of blue wings, when a white-breasted kingfisher parked itself on the deer’s back, right next door to the heron.

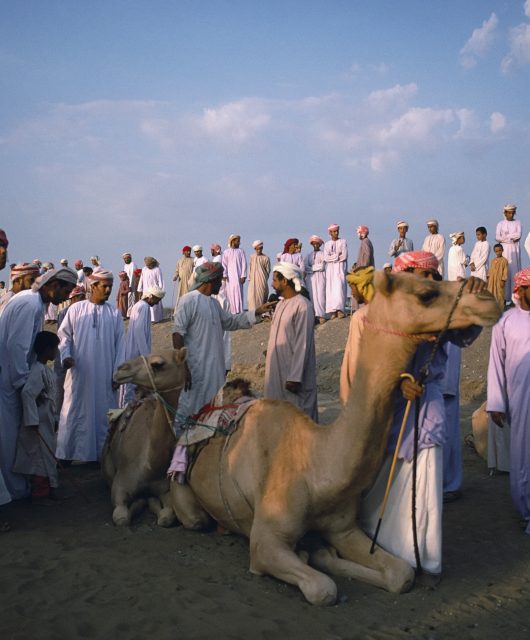

My next Tiger Reserve, Bandhavgarh, was a much smaller one, with much the same deciduous forest as Kanha (it is about seven hours’ drive away), but distinguished by an enormous fort at its centre. This national park was formerly the hunting precinct of the Maharajas of Rewa. Each ruler was expected to shoot 109 tigers and after the 109th there would be celebrations throughout the whole of his state. I stayed in the former hunting-lodge of the maharajas (built in 1962), which has four simple and spacious bedrooms and some comfortable tents. Although any recognition of royalty was abolished in 1971, the current Maharaja is still a considerable power in the area (getting elected to Parliament with majorities that run into the hundreds of thousands) and still owns the freehold of the lodge, which is now run by TigerTops. A characteristic princely retainer is in charge of the garden, and can often be seen squatting in a trance-like state among some ravaged marigolds.

There was a shortage of riding elephants in the reserve, because two of the four had been sent north to track down a man-eater terrorising an area about sixty miles away, where it had killed eight people (mostly wood-cutters) in the last two months. Tigers are not naturally man-eaters, but there will always be a very few who will develop this tendency. A man-eater may be an old tiger which has been bullied out of its natural feeding grounds by a younger dominant male. The dispossessed tiger may have difficulty feeding itself – perhaps because of worn-out teeth, or a festering wound from a porcupine. Alternatively, it may have been wounded in fighting the rival male. Whatever its handicaps, the old animal finds itself in ‘marginal’ territory with little of its natural food; so not surprisingly it turns to easier prey – usually villagers’ cattle, but just occasionally the villagers themselves. Once a tiger has become a man-eater, it develops supernatural cunning, refuses all poisonous baits, and terrorises an enormous area. Jim Corbett’s famous man-eater of Champawat killed 436 people before being shot in 1907. Now man-eating is far rarer, but a British ornithologist was recently killed in the Corbett National Park, when he strayed off the path in pursuit of the Great Indian Horned Owl.

In one part of India, the Swamps of the Sunderbans, on the border of Bangladesh, tigers seem to be especially prone to man-eating (about 450 people have been killed in the last decade), a taste that arguably they may have inherited. Here the authorities are trying a novel extension of aversion therapy: they have erected life-size models of wood-cutters and fishermen which give attacking tigers a discouraging 230-volt electric shock.

Although a visitor can go for days without seeing a tiger, my luck held in all three sanctuaries. On my second day at Bandhavgarh, we were driving up to the deserted fort (well worth the visit – numerous statues, armouries, stupendous water tanks, temples, all inhabited by only one priest), when a mahout with an elephant appeared from the forest. He had just seen a tiger and two cubs. I climbed onto the elephant from the top of the jeep, and we followed a steep nullah into the trees. Although we never got close enough for photography, I could clearly see two cubs playing and nuzzling each other. While I was watching through binoculars, a terrific rustle of leaves alerted me to a porcupine rushing towards us with its quills bristling, closely followed by the mother tigress. Just in time, the porcupine survived by closing its quills and darting under a stone.

The following evening no elephant was available, so Hashim, a wildlife expert and first-rate manager of the lodge, took me to a water-hole where we hoped to see plenty of game and bird life and, if we were lucky, a tiger into the bargain. There are over 220 species of birds in Bandhavgarh, many of a luminous colouring only to be rivalled by certain tropical fish, and these offer a great consolation if no tiger arrives. Many are wonderfully tame: it isn’t rare for a crested serpent eagle to return your gaze from only a few feet, while a racket-tailed drongo perches only just above your head. Only the jungle fowl scurries away – perhaps because, like so many game birds, he seems to know how good he is to eat.

On my last evening at Bandhavgarh I shared an elephant with Charles McDougal, the author of The Face of the Tiger. The mahout was making an extra effort to find him a tiger, and we went up and down steep hills and rocky ravines that even a mule would have found difficult. Often the clumps of towering bamboo were so thick that the elephant had to tear down a path with its trunk. Suddenly the mahout stopped the elephant, swivelled round and pointed at a hill. ‘Look,’ he said. We looked and saw nothing. ‘What’s there?’ I asked. ‘Tiger,’ he said impatiently. We scanned the hillside. By this time my eyes were accustomed to picking out well camouflaged tigers. I searched for a hint of orange, a black stripe, or the white spots on the ears, but neither McDougal or I could see anything. The mahout was becoming exasperated. ‘Look, look,’ he said, pointing again. We raised our eyes and this time saw, clear enough for the most myopic to see, a great tigress silhouetted against the sky. She stood gazing at us, with her chin nestling on a boulder. Eventually, she moved slowly over the hill. We followed further along, and as we reached the ridge, McDougal pointed – and there she was again. All we could see was a mostly-white face studying us over a pile of boulders. We used our binoculars, and could distinguish every hair on her face before she again sauntered away. This time we stayed still and watched her climb to the next ridge. Here she halted once more, turned to look at us, and presented a final magnificent silhouette against the evening sky.

In my fifteen days of tiger-tracking, I had the great luck to see twenty-two different tigers. Although this one was by no means the closest, she provided one of the great experiences of my life, and I would rather have watched that tiger than own a Rembrandt.

TRAVEL FACTS

Warnings

Until April, the game reserves can be far colder than you would expect. Take jumpers, a hat and some type of windproof jacket that will cut the wind when in the early morning you are in a jeep.

Don’t drive between Bandhavgarh and Ranthambore at night: the road is infested with bandits.

![]()

ADDITIONAL NOTES IN 2017

I don’t know if that road is still infested by bandits. But many people don’t realize the large extent of Indian territory which is controlled by Naxalites, especially at night. It is anyway a bad idea to travel on any Indian roads at night when, for a variety of reasons, you are far more likely to have an accident.

The excessive numbers of tourists will be very much worse than my description of Ranthambore, and will also now apply to Kanha and Bhandavgarh. If you wish to have a solitary view of tigers, do some very careful research, and your best information will be Word of Mouth.

The Jogi Mahal has for a long time ceased to accept visitors.

WHAT TO TAKE

Binoculars for each person are essential; also your own pillow, if you need a soft one to sleep on.

SEASONS

Many game parks are closed from June to November because of the rains. March is an excellent month (low vegetation and animals coming to the rare water-holes) but beware of the (moveable) feast of Holi, when the parks are either closed or likely to be filled up with transistor-playing visitors.

![]()

Articles by John Hatt

Other Articles

![]()

![]()