Fishing with cormorants in China

This article was first published in Harpers and Queen in May 1990

A cormorant fisherman in China earns more than five times as much as a university professor. The professor’s pay is £7 a week, whereas just one of a fisherman’s birds can produce an income of four times this amount. The practice of fishing with cormorants has continued for more than a millennium, and is still a thriving occupation in widespread areas of China.

To satisfy my curiosity about this extraordinary collaboration, I flew from Hong Kong to the River Li area, arriving at Guilin, a provincial city about a thousand miles south of Peking. This was a fortnight before the massacre in Tiananmen Square, and I was immediately struck by how much the country must have changed since the Cultural Revolution. In the bicycle-packed streets not a single person was wearing a Mao suit. Even as late as ten in the evening most shops stayed open, and neon-lit restaurants tempted Chinese and foreign tourists with caged displays of snakes, turtles and disconsolate pigeons.

From Guilin I set off with a translator for the small town of Yangshuo, 35 miles down the river, where we were able to arrange our first trip from a nearby fishing village. The next morning we embarked on two rafts made of stout bamboo, one for the 60-year-old fisherman with his five cormorants, and one for me with my camera. On reaching the fishing ground, the fisherman tied a length of rice-string around the neck of each cormorant to prevent the bird from swallowing its catch.

The fisherman picked up the birds by the neck – they are always carried in this way – and plopped them into the river. At first they swam aimlessly round the raft, like dejected ducks on a pond. Two of them decided to re-board and had to be dislodged with a nudge from the punting pole. In order to encourage them to dive, the fisherman jumped up and down on the raft, uttering a series of high-pitched gurgles, while splashing the water with his pole. One by one the birds began to dive. Every so often they surfaced with a wriggling fish, which they juggled head-first down into their long distendable necks. The fisherman approached, and if the bird was reluctant to be caught, he used a hook at the end of his pole to snare a knotted string attached to each bird’s leg. The cormorants’ necks were then manipulated until the fish emerged, and the birds were plopped back into the river.

The fishing sessions usually last about six hours. The birds are then fed with the smaller fish; or their collars are taken off and they are allowed to fish for themselves.

After one of our outings, we returned to the fisherman’s house where I questioned him about his work. He told me that the young birds are first brought down to the rafts at the age of four months. They are not immediately allowed to swim free, but are kept on a long line, while they learn from their elders. After only a month of training, they are set free to catch fish along with the other birds. There is no such thing as a useless cormorant: unlike, say, a gun-shy retriever, they can all be set to work.

I asked the fisherman whether he bred his own birds. His answer was typical of the financial acumen of the Chinese and the efficiency of their trade. The local fishermen usually get their young cormorants from the province of Shandong, 800 miles away. There the fish are especially cheap – seven pence a pound – so it is more efficient to transport birds over this huge distance, rather than feed them on local fish, which are ten times more expensive.

The most efficient working period of a cormorant’s life is between the ages of five and ten. Its life span is approximately twenty years; but somewhere around the fifteenth year, its eyesight starts fading and it ceases to be useful for fishing. Although the Chinese have a reputation for being unsentimental, they won’t slit the throat of such a long-serving servant. Instead they give the ailing cormorant a massive feast of beef, pork, and liquor, until it dies of excess. Even then the corpse isn’t chucked into the river, but is carefully buried. Before the 1949 revolution the birds were sometimes buried with full ceremony in a wooden coffin.

When the fisherman first told me this story, I thought it was the usual alluring nonsense that gets fed to credulous foreigners. But having talked to more than twenty fishermen in four separate communities, I heard the same story time and again.

The fishermen had little motive for teasing, impressing or misleading me. Although polite and amiable, they were entirely unimpressed that a foreigner had travelled seven thousand miles to question them about their livelihood. Nor was a single question ever asked about life in Britain. They always presumed that they would be paid for my lengthy questioning; and before any fishing expedition, we always agreed on payment in advance.

In between my sessions with the fishermen, I hired a bicycle for twenty pence a day and set off into the karst landscape, a fantastic scenery depicted by generations of Chinese artists. These paintings are in no way an exaggeration. In every direction, and as far as the eye can see, the countryside is scattered with near-conical green mountains, rising precipitately like overgrown termite mounds. Between the mountains, demure black buffaloes wallowed under towering clumps of bamboo, while straw-hatted peasants chaperoned ducks that waddled among an immaculate patchwork of vegetable fields. One ancient hunched labourer loosened the earth with a thin spade, helping the ducks to find some wriggling worms.

The villages, like the towns, are recovering from the regimentation of the Cultural Revolution; communes have been dismantled, and land returned to the farming families who are now allowed to grow crops of their choice. Once again the village doors are pasted with pictures of guardian deities, grimacing like Samurai warriors. These villages appear to be timeless, and indeed children may burst into tears at the sight of a foreigner, but they are not entirely out of touch with the modern world. Two friends of my translator ran a profitable business using motorbikes to bring video shows to the villagers, who are charged nine pence a session. The entrepreneurs sometimes can’t return home before 2am because a second film showing is necessary for the many villagers who work late in the fields.

At our next fishing village, Xingping, we arranged to join a father-and-son fishing team. They were in a downstairs bedroom, where the father was massaging the gammy foot of a forty-day-old cormorant. Three other young ones stood untethered on up-turned wicker baskets, from which they never moved even though they were nearly the size of full-grown birds. Their dung spurted out horizontally, almost entirely missing the baskets – presumably nature’s way of keeping the nest clean.

The fisherman’s son, who had long wavy hair unlike his father’s traditional short-crop, told me that he had just been fined £175 for fathering a second baby. His first child had been a girl, and he had risked the fine in the vain hope that his wife would produce a son. (In the cities many women now take a sex test for the baby, and abort any that are female.) Luckily the recent fishing had been good enough to pay the fine. The furnishings of their house – a large pedestal fan, a functioning wall-clock and colour posters of Chinese starlets – were evidence of comparative wealth. If he had needed to sell cormorants to pay the fine, he would have been paid about £90 for an average working bird, and more than £180 for an outstanding one.

I asked them to explain to me how wild cormorants are caught and subsequently tamed. To my surprise I discovered that the fishermens’ cormorants are an almost entirely domestic breed. I never heard of a single one being mated with a wild bird. The domestic strain has developed specialist habits and behaviour, in much the same way that a pointer has become different from, say, a sheepdog). Indeed the domestic ones have become so removed from the wild variety that there is rarely any need to clip their feathers: they seem to have lost the desire to fly.

Four hundred years ago, the concept of fishing with cormorants came to Britain, the idea almost certainly having arrived from China. In 1611, James 1 appointed a Master of Cormorants who was paid £30 ‘for his trouble in bringing up and training of certain fowls, called cormorants, and making of them fit for the use of fishing’. In the following year the Master of Cormorants was ordered ‘to travel into some of the furthest parts of the realm for young cormorants, which afterwards are to be made fit for His Majesty’s sport and recreation’. By 1618 the King had become so fascinated by the sport that he ordered nine ponds to be built close to Westminster Abbey, and also a special brick house for his cormorants and otters. (In remoter parts of China and Bangladesh, otters are still used for fishing.) The French kings also fished with cormorants, and we know that as late as 1736 King Louis XV, with a retinue in gilded coaches, used to watch his birds fish in the canal at Fontainebleau.

In the nineteenth century the sport was revived in England by the celebrated falconer, Captain Salvin. Unlike the Chinese, he didn’t use the domestic strain, and was therefore obliged to protect his face from bites by wearing an uncomfortable mask. A contemporary account gives a vivid description of local grandees watching his cormorants pursue trout in the Hampshire river of Mr Chamberlayne, ‘than whom a more hospitable man or more thorough yachtsman and sportsman does not exist’. During the Captain’s most successful progress, his birds caught 1,200 fish in 28 days.

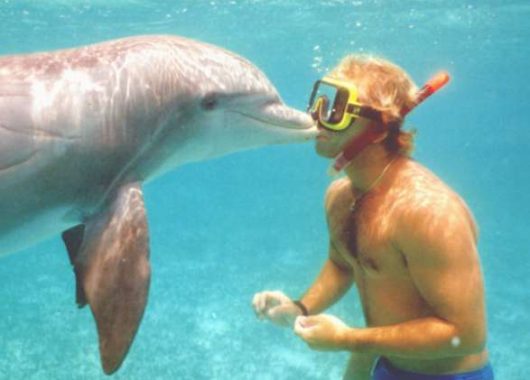

Our fishing expedition with the father and son was more spectacular than previous ones. Before releasing the cormorants, they first laid nets around a section of the river, thus making it more difficult for fish to escape. On this occasion their twelve birds needed no encouragement, as they seemed to sense that they had an improved chance of successful fishing. Almost immediately four cormorants surfaced with fish in their beaks. Other fish jumped out of the water, exciting the birds to further efforts. In an attempt to get good photographs, I jumped into the water and got a close view of the birds swimming below me, one of them streaking between my legs. It was wonderful to see them swerve in pursuit of fish; cormorants are ungainly on land, but under water, they are as streamlined as a shark.

Occasionally one of the birds caught a fish which was too large to swallow, and then the other birds rushed to get a grip on the same fish until the fisherman retrieved it. The scant literature on cormorant fishing often describes this phenomenon as the cormorants ‘helping each other’. But my firm impression was more of the birds just wanting to get a share of the action. Cormorants are very clever at their main task which is fishing; but their intelligence may have been exaggerated. After all, they go on and on enthusiastically catching fish which they are never allowed to eat.

Occasionally one of the birds caught a fish which was too large to swallow, and then the other birds rushed to get a grip on the same fish until the fisherman retrieved it. The scant literature on cormorant fishing often describes this phenomenon as the cormorants ‘helping each other’. But my firm impression was more of the birds just wanting to get a share of the action. Cormorants are very clever at their main task which is fishing; but their intelligence may have been exaggerated. After all, they go on and on enthusiastically catching fish which they are never allowed to eat.

Previous writers have been partly misled by the fishermen’s habit of giving the birds an individual name, as one would a dog. These names are only for identification purposes, not for giving orders to a particular bird. Although a fisherman can order his cormorants to board a raft (I checked this by asking one to do it), he cannot, for instance, order Peng to come aboard, while ordering Wang to go on fishing.

Sometimes, in winter when the water is clear and cold, a cormorant can apparently catch an enormous fish, as large as fifteen pounds. In May there is too much water so I couldn’t witness this; but having seen a caged carp of approximately five pounds, I had the opportunity of testing whether a cormorant would pursue a fish that is several times the size that it can usually swallow (about three-quarters of a pound). I asked the fisherman to untie his best bird, and then release the fish. The point was soon proved. With the keenness of a terrier after a rat, the bird plunged into the water and soon brought the thrashing fish up to the surface.

Sometimes, in winter when the water is clear and cold, a cormorant can apparently catch an enormous fish, as large as fifteen pounds. In May there is too much water so I couldn’t witness this; but having seen a caged carp of approximately five pounds, I had the opportunity of testing whether a cormorant would pursue a fish that is several times the size that it can usually swallow (about three-quarters of a pound). I asked the fisherman to untie his best bird, and then release the fish. The point was soon proved. With the keenness of a terrier after a rat, the bird plunged into the water and soon brought the thrashing fish up to the surface.

Being mystified by the East European taste for carp, I have tried the fish on several occasions and always found it to taste muddy. Now, I handed the five-pound fish to my Cantonese translator (the Cantonese are reputed to be the best cooks in China) to see what he could achieve. Our hotels never seemed to mind him entering their steamy kitchens, where he interfered with the cooking and even prepared whole dishes with our own ingredients. For lunch we ate a delicious soup made from the carp’s head. Before dinner he sliced open the fish, before marinating it for half-an-hour in ginger, soy sauce, chives and Chinese liquor. Then he fried the fish in oil, tomatoes, a little sugar, more soy sauce, adding onion shoots at the end. It was delicious.

We left the village, travelling more than two hundred miles to the precipitous rice terraces in the tribal area near Longshen. In one of the valleys we found two cormorant fishermen prepared to talk with us. They were another father-and-son team, but their family (a tribal one) had been fishing with cormorants for only five generations. Because they were not going to begin fishing until dark, we had plenty of time to discuss both tactics and concepts while sipping bowls of cinnamon tea. I repeated the questions that I had asked to the previous father-and-son team, and their answers proved to be almost identical.

‘Do you enjoy your work?’, I asked.

‘It is our work; that is why we do it.’

‘I quite understand. But although most people do their work just because it brings them money, a lucky minority get pleasure from this work. Are you one of this lucky minority?’

When the father answered, the son nodded in agreement: ‘We have no land. Fishing is all we know. It is our profession’.

This was still inconclusive, so I pursued it further. ‘If you had land, would you like to stop fishing?’

‘Yes, if we had land, we would rather be vegetable gardeners. That occupation would be far more secure’.

![]()

Articles by John Hatt

Other Articles

![]()

![]()