Syria

This article was first published by Harpers & Queen, October 1992.

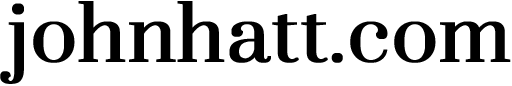

During my background reading on Syria, I discovered that all the millions of hamsters that have been kept as pets are descended from one single pregnant animal, which was trapped near Aleppo in 1930. Apparently, only ten more wild hamsters have ever been caught, all of them within the vicinity of two villages. I was so intrigued by this fact that, although Syria is one of the most spectacular sightseeing countries in the world, I resolved to spend some time discovering if the villagers were still trying to catch these elusive animals.

After a few days travelling I still hadn’t met anyone who had ever seen or heard of a hamster, not even in Aleppo. Therefore, after finding a retired Professor of History who, for a very reasonable fee, agreed to act as my guide and translator, I decided to go to one of the two villages. The professor suggested that we first visit a friend of his, a paediatric doctor who had hunted all his life and knew everything about wild animals. We took a photocopy of a hamster’s photograph from Petit Larousse and went to the doctor’s surgery, where after prodding a few babies, he studied the photograph and announced that he had definitely never seen such an animal. He did say, however, that only yesterday he had seen a street-hawker using a similar type of animal for telling fortunes.

After a search through the streets, and much questioning of other hawkers, we found this man standing on a crowded pavement behind an up-turned box. In fact he was using guinea pigs. At frequent intervals passers-by gave him a coin, and he would then slowly move a guinea-pig over a forest of folded bits of paper. When the animal grabbed one, it was handed to the customer who nonchalantly read his fortune. My own fortune read, “You don’t distinguish between friends and other people to whom you give your problems. Beware, they are jealous of you. Beware of them always: they will destroy you. But God will save you”. We started to ask the hawker about hamsters, but our discussion attracted such a crowd of customers that he suggested we adjourn to a nearby courtyard for some tea.

Although he had used five similar types of animal for telling fortunes, and though he caught many of his animals in the wild, he said that he knew nothing about wild hamsters. Of all the animals he had worked with, these guinea-pigs were the best. They never bit, and they took only fifteen days to train. He told us that he led a very peripatetic life, because after a few days in any city, the novelty of his method of fortune-telling dropped off, and he was obliged to move on. He travels with his guinea-pigs throughout the entire Arab world, and occasionally has even gone further – to Afghanistan, Pakistan and India. When I asked him which city has been the most profitable, he replied without hesitation,”Beirut”.

Since even this expert knew nothing about wild hamsters, we set off for the village of Benjamin, where some of the first ones had been caught. The village was now separated from the outskirts of Aleppo by only one flat green field. The ramshackle streets were empty of people, so the professor went straight to the mosque, where we found a local cleric, a regal black-turbaned figure squatting on a carpet next to a saint’s tomb. He was saying prayers over a woman’s bad back, and he asked us to return later. When we eventually joined him on the carpet, the professor explained at length the saga of my search for the hamsters. The cleric replied that, indeed, he knew these animals: they were very bad for Muslims, they were dirty, and they ate the villagers’ crops. He added that he killed them whenever he could. After further questioning it turned out that he was talking about rats, and that he had never seen or heard of a hamster. He recommended that we ask an old man in the village, who might be able to help us.

This old man appeared alarmed at our arrival, but he knew at once what we were talking about. And he certainly wasn’t inventing things, because he clearly described something that he wouldn’t have imagined – the two pouches on either side of a hamster’s face. He said that the villagers described the animals with an Arabic word meaning “saddlebags”. He sees hamsters quite often, especially during the lentil harvest. They are easy to catch, but he had never heard of anyone keeping them as pets, or even eating them.

It was clear that the Syrian hamster still survives in the wild; and when my driver learnt about the pouches, he reliably informed me that he had seen the animals in his own village (which is also in the Aleppo area). But wild hamsters must be extremely rare: I never met anyone else in Syria who had come across them – not even some gypsies who invited me for tea in their tent. Although they had hunted the length and breadth of Syria, they had never seen a hamster.

After returning to Aleppo, the professor took me to the souk, which dates from the time when the city was an important crossroad on the great trading routes. This souk must be the most enticing in the Middle East. Its miles of cobbled passageways are still covered with seventeenth-century vaulted roofs, and along the sides of the passageways you can still see enormous studded doors leading to the courtyards of ancient caravanserai. Most of these have always been owned by Christians. I climbed the stairs in one courtyard to visit a spacious flat, which had been continually inhabited by a Christian family for more than four hundred years. After going through the front door, the noises of the bazaar were banished: all was dignity and calm. Long passages led to rooms formally furnished with European furniture and paintings. In the dining room, which could have been in France, I opened a small shuttered window; immediately a blast of noise from the souk entered the room, and I could look down below at a row of cobblers.

The souk in Aleppo is more exotic than that of Istanbul, and still has an oriental character that is fast disappearing from so much of the Middle East. Unlike Istanbul, many of the goods in the shops are still delivered by donkey, and whenever a donkey appeared, I couldn’t resist taking a photograph. Later during my trip I became ashamed of my camera work, after several Syrians had asked me whether I intending to publish the usual hackneyed photograph of a donkey in a bazaar. And, anticipating the usual photographs of veiled women, they pointed out that fully veiled women in Syria are nearly always pilgrims from Iran.

This is not a trivial matter. Syrians are deeply irritated that their country is so often represented as being mediaeval, when in so many respects it is up-to-date. They are right to be irritated: those donkeys may have been a thrill for me, but they are in no way representative. You could spend days in Syrian cities without seeing one donkey; a dual-carriageway would be more representative.

The problem for the travel writer is that those aspects of a country which make the locals proud – the new schools, the hospitals, the factories – are too similar to what we have at home; but our search for the picturesque and the unusual means that we are increasingly likely to misrepresent the countries we visit. We are more stimulated by the exotic, and our liking for the exotic is reinforced by the certain knowledge that it is getting rarer. We like the donkeys because they represent centuries of traditional life, which we know will soon disappear. And, as the exotic increasingly disappears, some of our travel writing tends to become increasingly misrepresentative.

It must be admitted that, to Western eyes, modernity in the developing world has often replaced beauty with ugliness. The typical Syrian village has in recent years become an unplanned mess of concrete and breeze-block houses, all of which have tangled metal rods, like nose-hairs, sprouting from the roofs. On the other hand we should remember that this unsightly rash of building has without doubt improved the lives of the inhabitants. Not many years ago, most of the villagers of northern Syria lived in conical dwellings, the shape of mediaeval beehives; these were delightful to the eye, but cramped for the owners. Now the villagers have more space as well as running water (though their new houses aren’t as well insulated against heat and cold). On the outskirts of Aleppo I pointed out to my driver a hideous conglomeration of medium-rise flats, which had been built in the same style as our worst housing estates of the 1960s. When I asked him what he thought of them, he replied that they were magnificent.

Modernity is even starting to blight the perfect beauty of some of the country’s most celebrated archaeological remains. A municipal-style wall has been erected at the back of the wonderful roman theatre at Palmyra; unsightly glass doors have been inserted into the theatre at Bosra; ugly villas are starting to speckle the hill next to the magnificent crusader castle at Crac de Chevalier. Much good restoration work has been done, but it isn’t always aesthetically pleasing.

Although travellers will sometimes be depressed by the ravages of the last decade, this will be more than compensated for by the charm of the Syrians themselves. Everywhere the visitor is greeted with joy. In every corner you hear the words: “Welcome”, “Welcome you”, or “Welcome to Syria”. Everywhere you are safe, probably several hundred times safer than in New York . You aren’t hassled be shopkeepers or cheated by taxi-drivers. And so many people invite you for coffee or tea that after a few days you suffer from acute caffeine poisoning. I soon learnt not to ask strangers for directions to a restaurant, as this inevitably led to an immediate invitation for a gigantic feast in a private house. It is likely that some of this exuberant friendliness to strangers will diminish when more tourists come to Syria; but the tradition of hospitality runs deep. At the Palmyra Museum, which must receive more tourists than anywhere else in Syria, I was spontaneously invited for tea in the ticket office. And the tradition of courtesy is also resilient: an American expatriate, who had lived in Syria all through the recent years of hostility, told me that he had never once received any personal abuse.

The Syrian I got to know best was my driver, Abdel, who was as friendly and kind as all the Syrians I met. He was quite critical, though, of some aspects of my character. About every two days he reminded me that my bachelor status was a disaster. He, himself, at the age of twenty-two had married a girl of sixteen, and had now had ten children who would look after him in his old age. He was also shocked by my insistence on using a seat belt (and a policeman in Aleppo also ticked me off for this unmanly act). Abdel did eventually use his seat-belt a few times, but I suspect this was a subtle act of courtesy. He was also worried about my habit of reading too much. “Why are you always reading?”, he would say. Or when more exasperated, “Reading, reading, reading! After, you tired. One day you go crazy. Your head will go kaput.” However, the only times I saw him genuinely exasperated were during our discussions before lunch. As the hour approached, he would say “Today I will pay for lunch”. Remembering those ten children in Aleppo, I would reply “No, Abdel, you paid yesterday. Today I will pay”. Then in a slightly vexed tone Abdel would reply “No I will pay today”. Then I would say “Really Abdel, it’s much better if I pay, then my magazine will pay for both of us. It won’t cost me a penny”. For some reason this would enrage him, and he would start hitting the steering wheel and cursing the magazine. So Abdel bought most of our lunches, and it was only with considerable dexterity and diplomacy that I managed to pay for a few.

![]()

From the wonderful choice of excursions out of Aleppo, the most impressive is the basilica of St Simeon Stylites. This beautiful sandstone building, the colour of the best Cotswold stone, was built in the Fifth Century around the pillar on which the saint lived. Although the story of the pillar is astonishing, it is well attested by contemporary accounts. After the Edict of Milan in 313 AD, Christians were no longer persecuted, and therefore the most austere of them felt the need to mortify themselves. Simeon practised several mortifications, including wearing a spiked girdle, and burying himself up to his chin during the summer. Gradually he became an object of veneration, and attracted pilgrims. In order to withdraw from them, he built himself a column to live on; but the crowds grew larger, and he was forced to build himself increasingly tall column, until he built one that was more than 60 feet high. He lived on top of this for 37 years until his death in AD 459. By then he was attracting huge crowds of pilgrims, some of whom came from as far as London and Rome. Although provisions were hauled up to him in a wickerwork basket, his life must have been extremely uncomfortable, for in this part of Syria it is freezing in winter and scorching in summer. Despite the discomfort, he started a fashion for withdrawal-chic, and during the next few hundred years, Stylites popped up all through the Middle East.

When I arrived at the basilica on a Friday, the Islamic weekly holiday, it was filled with Syrians, for they love to make a party out of visiting their monuments. Some groups had brought their own bouzoukis, others were dancing in circles. Crocodiles of children jumped at the opportunity to shout “Welcome” at a foreigner. But there was one foreigner who wasn’t joining in the merriment – a red-faced Frenchman, who was shouting at anyone near St Simeon’s pillar; he wanted a photograph uncluttered by human beings. When Abdel – accustomed to helping foreigners – also started to clear people out of the way, I told him not to help, adding that the foreigner shouldn’t be so obnoxiously bossy to people in their own country. At which the Frenchman turned to me and politely said, “But I know these people; I’ve lived here for months”. “What is your job?” I asked. “I’m a diplomat”, he replied.

The French used to be the colonial power in Syria, and they are keen to maintain a considerable presence. After the Allies had betrayed the Arabs at the end of the First World War – we promised Independence in return for their help against the Turks – Syria was grabbed by the French.

The basilica of St Simeon may be the most impressive building near Aleppo, but there are enough other sights to keep any lover of ruins happy for years. In this region there are reckoned to be more than 700 ghost towns from the Roman and Byzantine era, and an unequalled number of early Christian churches. The area must hold the greatest concentration in the world of ancient remains, and because there are as yet no detailed guide books of Syria, you can be alone in them. Even when the guide books finally arrive, they can’t possibly spoil the area, because there is an unlimited number of ‘Dead Cities’ that are far from a road; so if you are prepared to walk or ride, you will always be able to picnic in your own Roman ruins, and to remain confident that no-one is likely to choose the same spot for another decade.

When I visited three large Roman towns, complete with villas, sepulchres, temples, olive presses and inns, I found that only the roofs and even these had survived on some of the more spectacular tombs. In all these towns, two of which covered an area of several square miles, there were no ticket offices, no signs, no dustbins, and not one single visitor. The only human beings I saw were a few peasants who lived in the buildings, or used them as stables. There is such an abundance of ancient remains in Syria that the visitor has the excitement of finding ones which aren’t treated with museum-like reverence. Clothes lines are suspended between Greek columns; Roman tombs are used as slabs for cooking. An archaeologist told me where to find a magnificent two-storey Roman villa that has been in continual occupation for 1,700 years. When I found the house, the peasant farmer living in it took me through a large door into a dark vaulted hall where a cow was stabled. I shone a torch at the ceiling, and could see Roman heads sculpted on the arches. In the bedrooms the family keep their paraffin lamps in elegant wall-niches carved with scallop shells.

After several days of exploring the North, and a drive into the desert to spend three nights at the world-famous Roman city of Palmyra, we drove to the southern city of Bosra, once the capital of the Roman Middle East. On the way, Abdel wanted to make a call on a Christian friend with whom he had done his National Service. His friend lived in a green one-storey house, surrounded by a spacious garden. Cardamon-spiced coffee was immediately produced from a thermos – Syrians are always ready for unexpected calls – and soon afterwards some of his twelve children produced tea, biscuits, and cigarettes. I admired their budgerigars, and the cage was at once placed in front of me for my enjoyment. Even during the hour we were in the house, there was a constant flow of other callers – cousins, friends, neighbours – all of whom were served coffee.

At the back of the friend’s house we could see the snow-capped mountains of the Lebanon, and it was impossible to forget that only a few miles away Christians and Muslims were recently killing each other. In Syria, there is a large Christian minority (including Maronites, Evangelists, Roman Catholics, Greek Catholics, Syrian Orthodox, Greek Orthodox, and so on ) but they live side-by-side with the Muslims without fear, even in the fundamentalist city of Hama.

Defenders of the Syrian regime, which is a ruthless one, point out that Syria is full of minorities – Armenians, Bedouins, Kurds, Alawis, Christians, Druze, even a few thousand Jews – and that a ruthless hand is necessary to prevent chaos. You are certainly made aware of presidential omnipotence. Everywhere, but everywhere, you see photographs of President Assad, looking like a benign Austrian uncle. His face is on banners, flags, posters, heart-shaped stickers, and stencils. Every shop displays at least one of his photographs, and usually rows of them. The back windows of cars are often obliterated by his beaming face.

Assad has tended to favour state-socialism, which has brought the usual advantages and disadvantages. The country is quite poor, and suffers from the excessive bureaucracy, inefficiency and drabness that characterise rigid state control. On the other hand, by the standards of many comparable countries, there is high level of literacy and a good health service. No-one starves, and families get a ration of tea, oil, sugar and rice for each child (this may also be a partial explanation of why there are so many huge families). You don’t see the degradation and the grotesque deformities found, say, in Morocco.

Assad now appears to be moving away from the excesses of central planning, and if you aren’t on the wrong side of the government, it is possible to avoid some of the irksome regulations. Although fax machines, for instance, aren’t allowed (presumably because they aren’t as easy to monitor as telephones) an expatriate in Damascus told me that he had managed to keep a fax machine by giving the Security Services a duplicate that would record for them all his ingoing and outgoing messages.

![]()

The massive Roman theatre at Bosra, which can hold 15,000 spectators, is the best preserved in the world. It is built out of black basalt – an immensely hard stone, far harder than the beautiful sandstone of the North. This astounding edifice was further saved from dilapidation by the construction of an Islamic fort around it. My first visit, when I had the place to myself, was breathtaking, but my second was the most enjoyable. Again, I happened to arrive at one of the country’s great monuments on a holiday. This time the crowds were even more festive; thousands of people were pouring into the theatre for a gigantic near-communal party, with the sounds of bouzoukis, drums, and bagpipes resounding throughout the stone auditorium. The Roman seats were packed with groups of people licking ice-creams, posing for photographs, and watching circles of women dancing impromptu on the stage.

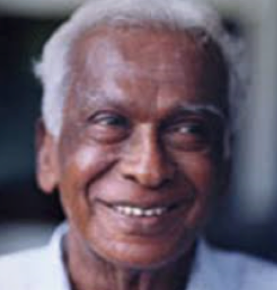

A few miles north of the theatre is the territory of the Druzes, and I decided to make a call on one of their principal chiefs, Mansur al Atrash, the son of the famous Sultan al Atrash who had led a fierce rebellion against the French in the 1920s. I wasn’t too worried about making an unannounced call: Druze chiefs keep special rooms devoted entirely to receiving guests.

There are more than a million Druze in the world, most of them being in Syria and the Lebanon. Their religion, an offshoot of the orthodox Islamic mainstream, began with a cult of the mad Caliph al-Hakim in the Eleventh Century. Since then the tenets of their faith have been kept secret, and are revealed only to certain qualified elders. The public elements of their theology differs from the mainstream of Islam in several ways: they believe, for instance, in reincarnation. They don’t believe in conversion, and no-one can become a Druze unless they were born as one.

Their sense of community is famous, and it is said that a Druze would rather marry a poor relation than a rich stranger. Traditionally they are indomitable fighters, and during the Druze rebellion against the French, a fifth of their menfolk were killed. Those who employ Druze tend to speak of them with affection and admiration.

Our search for the house of Mansur al-Atrash began in Suweyda, the Syrian Druze capital. Here, where almost everyone is a Druze, you see why they have such a reputation for beauty. The women have long regular faces, blue eyes, lustrous cascades of black hair, and pale olive complexions tinged with bronze. The men are at their most handsome after the age of forty. At this time of their life many of them decide to become an `uqqal’ – a type of religious elder. They then shave their head, wear a pair of black baggy trousers, a white headdress, and grow a huge silver moustache. They look like magnificent mountain warriors.

Even though Mansur al-Atrash was leaving his house when we arrived, he concealed any annoyance, and invited me and Abdel for coffee. Soon afterwards his wife joined us for tea with biscuits. At first we chatted agreeably about his trips to London and Paris, and he revealed that he feels more at home in Paris, despite his family’s rebellion against the French.

Because he had served as a Cabinet Minister in several Syrian governments, I brought the subject round to politics. Did he agree with me, I asked, that the goal of Arab unity was as futile as the goal of European unity. Curbing the irritation he must have felt, he very gently informed me that his most heartfelt wish was for Arab unity, and that his entire political life had been dedicated to this cause.

After our chat, Mansur announced that he had been invited by a Christian neighbour for lunch, and that we would be welcome to come along. We drove to the neighbour’s house where we joined fifteen other guests who were seated on benches round the edge of the room. Although this was a Christian household, there were no women present. Most of the men wore Arab headdresses, but two wore baseball caps. After coffee and conversation, a pitcher of water was circulated so that we could wash our hands, and then an enormous circular metal dish was placed in the centre of the floor. Eight of us were the first to squat round it, and we ate succulent mutton mixed with yoghurt and unleavened bread.

When the time came for us to depart, Mansur al-Atrash made a great fuss of Abdel, embracing him warmly. Although in the Arab world democracy hasn’t taken much of a root at government level, it is frequently noticeable that, in their day to day relations with each other, Arabs are more genuinely democratic than ourselves. (I leave aside the large and complicated question of the status of women.) Whenever I made a call on a Syrian, Abdel was automatically invited as well. And while we were making a call on another Druze chief, Abdel felt free to tick him off for smoking too much.

![]()

When reading a 1950s book about Syria, I was intrigued by a remarkable method of hunting, involving a complicated co-operation between man, hawk and hound. Although this was an unrepresentative feature of Syrian life, I couldn’t resist investigating it. However, this method of hunting no longer existed and, as a consolation, a kind diplomat gave me the address of Mr Badr al Barazi, who still hunts hares with salukis. These are the beautiful greyhound-like dogs that for many centuries have been bred for hunting by sight in the desert. A representation of one has been found on a five-thousand-year-old coin at Nineveh. Formerly they were used to hunt gazelle, especially by the Bedouins, but now they are mostly used for hares. Although Salukis don’t have the speed of a greyhound, they have far more stamina.

I telephoned Mr Barazi from a hotel in the devout city of Hama, and was immediately summoned to his flat in a prosperous suburb built around a new mosque. He was an imposing man with a seigneurial face, dressed in a black robe edged with gold. He led me into a sitting room decorated with a formal arrangement of gilded European furniture, where we drank the usual spiced coffee. He told me that the hunting season had come to an end, as it was now growing too hot; but with characteristic Syrian hospitality, he said he would make a special effort for me, and that I must spend the night so that we could go hunting early next morning.

After I had brought in my bags, we went to call on a convalescent son, who had fallen off a horse and broken his leg. His bed had been moved to a sitting room, where a television was quietly playing an Arab melodrama; several visitors, all dressed in headdresses and robes, were sitting round the edge of the room. These were prosperous burghers of the community; in the daytime they abandon their robes for western suits. Many of them stayed only a few minutes, as space had to be made for the constant stream of new arrivals. I asked the bed-ridden son if there were always so many callers. “Yes” he replied contentedly, “I get about 150 visitors a day”.

When most people had left, Mr Barazi took a carpet off one of the chairs, knelt on it and prayed. He then parted his robe and showed me an enormous scar on his chest, a result of open-heart surgery in Houston, Texas, where he has twenty-three cousins.

Very early next morning we were joined by another son, and then drove through a prairie-like landscape of smooth hills, dotted at this time of year with the low black tents of Bedouin. We eventually drove off the road and parked by an unfenced field of young wheat.

The three of us then walked in line across the stony hills, keeping about thirty yards apart from each other, while the dogs trotted about sixty yards ahead. They kept scanning the view, even though during our two-hour walk we never once caught sight of a hare. Occasionally they paid mild attention to the shouts and whistles of Mr Barazi, but otherwise they ignored him. I had read in England that salukis were strangely unbiddable dogs, which appeared to be true. Perhaps this is because during their generations of ownership in the Middle East they have never been much petted by their owners. Most Muslims wouldn’t dream of keeping any dog, except for a saluki, and even these aren’t kept as pets. Dogs are considered to be dirty and un-Islamic. In fact many Muslims would be surprised to know that there is no condemnation of dogs in the Koran.

When the sun became too hot for the dogs to hunt, we squatted on the ground next to some miniature red tulips, where we ate a breakfast of unleavened bread, apricot jam, and refreshing sheep’s yoghurt. We then returned to the flat in Hama.

During my stay in the flat, I never saw Mr Barazi’s wife, who remained concealed, which must have been inconvenient for her. Occasionally I heard her rushing from room to room. But when we returned from hunting, two vivacious daughters were far from concealed, and joined us for coffee in the drawing-room. They told me that they were studying the English Language, and that they had recently been reading Shakespeare, Ben Johnson, and Dryden. But although they were freer than their mother, they had by no means repudiated their religion. After polite and friendly chit-chat, a new tone entered our conversation. They explained to me that the Koran is very relevant to the modern era, and that it is definitely good for women. They said the reason for the veil – where it exists – is so that the beauty of women won’t tempt men away from their wives. And the daughters said that even when men do fall for another woman, then the matter is arranged better by Islam: the man doesn’t abandon his first wife, but instead takes the new woman as a second wife. “So at least every child knows who its father is”.

Each daughter interrupted each other to give examples of the superiority of the Islamic way of living. “Our families are much closer than yours. Look at how you treat old people. And we have a cousin who has married a girl from Bournemouth. She has converted to Islam. She has told us that when she goes back to stay with her family, they make her pay rent. We could not believe such a thing. And another thing, you Westerners think all of us Arabs are backward, that we live in tents, and have long fingernails and dirty hair”. My denials were brushed aside. “Oh yes you do. We have relatives all over the world who tell us these things. I was so angry when I first heard them.”

This is a refrain that I’ve frequently heard; but the ear-bashing never lasts too long, because the resentment isn’t personal. By the time my driver came to take me away, the sins of the West had been forgotten, and the eldest daughter was saying, “We have so much enjoyed this conversation, and we are looking forward to another one. You must come again. Now that you are part of the family, you can come back at any time that you like.”

![]()

TRAVEL FACTS.

When this article was first published in 1992, the Travel Facts were more extensive. I have erased much of the material that is no longer interesting or relevant. All the same, I have retained the following sections, partly because the recent years of tragedy have given them a certain poignancy.

EXPENSE.

Most items in Syria are cheap, and taxis, for instance, are stunningly cheap. A short taxi ride, for instance will cost only 20 pence. However, owing to an archaic legacy of state bureaucracy, foreigners are made to pay a special rate for hotels. Independent travellers should check if this rule still exists, as it can make hotels expensive. Most of these anomalies are now being abolished.

BOOKS AND MAPS.

As I write the only guide book to Syria is the skimpy Jordan and Syria by Hugh Finlay (Lonely Planet). Two guide books are on the way: Syria, a historical and archaeological guide, by Warwick Ball (Scorpion) and Monuments of Syria by Roff Burns (I.M. Tauris). Daunt Books (83 Marylebone High Street, London W.1. Tel: 071 224 2295) stock the above books and The Druze by Robert Brenton Betts (Yale).There is no first-rate map of Syria, but it is still best to buy one before you go. The clearest, which also included town maps of Damascus and Aleppo, is published by GEOprojects, and is also available from Daunt.

CHOOSING YOUR TOUR GROUP.

If you are going on a tour group, check on the numbers, because I have heard of one group that included 44 people, which is too many. Check that you aren’t rushed through too many sights, with no opportunity to relax. If your organised tour includes only one night in Palmyra, this will be a bad sign. Many tours include Petra in Jordan, owing to its extreme fame. If you will have another chance to go to Jordan, consider carefully whether you want to exercise this option, for there is more than enough to keep you busy in Syria.

INTERPRETER/GUIDE.

If you have a serious interest in an aspect of Syrian culture, then the charming Dr Mahmoud Hretani, may be available for a fee, when he isn’t teaching. He has written a thesis on the souks of Aleppo, so he would be especially interesting about these. You will need to understand French.

HAMSTERS.

I wrote to the letters page of BBC Wildlife magazine, asking how hamsters are so healthy when they are all descended from one set of incestuous brothers and sisters. The crux of their published reply, which I think I understand, ran: “Chronic inbreeding greatly accelerates the process of exposing and eliminating those defective genes from the population through the early deaths of the carriers. This means that the populations which have been inbred for many generations can be relatively free of recessive mutations, making them very healthy”. In recent years new types of ‘hamster’, such as the Dwarf Chinese, have been sold by pet shops. These aren’t true hamsters and can’t interbreed with them.

WOMEN.

They are respectfully treated if sensibly dressed. Skirts should be mid-calf. A large scarf is necessary for mosques, and would be appreciated in rural areas.

WEATHER.

The hot weather tends to begin in May. It can be alarmingly cold before then. By the middle of June it will be very hot. The heat continues until September, when there may be rain; but it is generally considered a nice month. October and November tend to be rainy. December and January are very cold. February starts to be a bit warmer. In March and April there plenty of wild flowers.

MISCELLANEOUS TIPS.

In the Damascus Museum you will see a rope blocking the staircase down to a Palmyran tomb. Try to sweet-talk a museum warden into letting you through, as it is really impressive. It is not true that the Azem Palace in Hama has been completely destroyed, and it’s well worth a visit; in a dim room you will find a stupendous mosaic of female musicians. Three Dead Cities that I greatly enjoyed were al-Bara, Serjilla, and Ruwaiha; they are all quite near each other, so take a picnic. Make sure you see the astonishingly well-preserved section of Roman road near Aleppo. I remarked to a guide that this must surely have been restored; and he replied “Yes I’m afraid it has been – by Marcus Aurelius in 162 AD”.

![]()

Articles by John Hatt

Other Articles

![]()

![]()